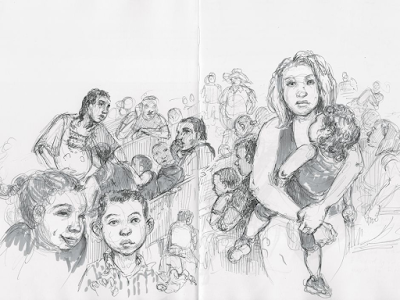

Scenes From an American Tragedy: The Border Crisis, Doctors Have a Name for Separating Kids from Their Parents at the Border: It's Torture.

Scenes From an American Tragedy: The Texas Border Crisis,

Some parents even contemplated suicide.

Doctors Have a Name for Separating Kids from Their Parents at the Border: It's A Form of Torture.

More than 2,300 children were separated from their parents through Donald Trump’s “zero tolerance” policy before it was suspended on June 20th. In July, I spent five days with my sketchbook in the Rio Grande Valley, the epicenter of the border crisis, and found an immigration system returning to its status quo – which even without family-separation is one of daily cruelty and heartache. Children were no longer being ripped from their mothers and fathers; families were incarcerated together, sleeping on bare concrete in packed processing centers, nicknamed hieleras, or “iceboxes.”

“They humiliate us,” a mother from Honduras told me at the McAllen bus station, where hopeful but exhausted migrants go after their often-traumatic initiation into the U.S. immigration system. “With sticks, they beat the metal bars to wake us up. If the children cry, they go after us. There was a child with a fever. They bathed him in cold water and let him lie naked on the floor except for his underwear. The mother was crying because the child is crying. She wants to cover him, but guards tell her she can’t.”

From the moment they’re seized at the border, immigrants move through an archipelago of institutions — Customs and Border Patrol, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Executive Office of Immigration Review — and at each point, they are guarded, shackled and transported by private contractors working for Ahtna, Trailboss and G4S. When I presented allegations of mistreatment to spokesmen from Customs and Border Patrol, they did not respond to my request for comment.

This alphabet soup of agencies does not make it easy for the media or anyone else to witness the detention centers and courtrooms that “process” the humans who cross the border. Officers withheld information from me about rules for visiting facilities, and presented elaborate, shifting requirements for access. On my first day reporting, I had permission to visit the Port Isabel Detention Center in Los Fresnos, where detainees work in the cafeteria and scrub toilets for $1 a day (a can of coke at the commissary costs $1.75). Port Isabel’s record of human rights complaints stretches back years; in 2010, inmates launched hunger strikes over medical neglect and the lack of legal aid, and a former guard wrote a memoir detailing the facility’s history of corruption and abuse, comparing it to Guantanamo Bay.

When a friend drove me up the unpaved detour road and past the barbed wire fences to the gate at Port Isabel, the guard said my friend wasn’t even allowed to drop me off since her name wasn’t on the list. Nor could I walk. When I asked to see the rule that forbade walking, the guard began patting his holstered gun. My only option, I was told, was to drive away and take a taxi. It cost $30 for a 10-minute ride (two taxi companies have a monopoly on visiting Port Isabel). “Imagine being a semi-traumatized Guatemalan woman just released, with no cash,” community activist Michael Seifert tells me. “This happens all the time. I don’t know why they can’t give them a ride.”

After my first day sketching at the Port Isabel court, the Executive Office of Immigration suddenly sent a directive to other courthouses that forbade drawing without prior permission. It promised federal penalties for artists who did not comply. When I arrived at the Harlingen immigration court the next day, the new directive was already taped to the wall and highlighted. “Just got it yesterday,” a guard shrugged.

In the evenings, I went to the bus station, where there were no restrictions on sketching and families were free to tell me their stories. They were the lucky ones. They had been released from the hieleras to family in the U.S. to pursue their asylum cases from a home rather than a cell (some families are instead locked up indefinitely in longer-term detention centers). Most of the migrants at the bus station wore electronic ankle monitors, which ICE uses to keep track of asylum seekers through its “Intensive Supervision Appearance Program,” run by a private-prison company. Many spoke with me but were scared to share their names for fear of the gangs they’d fled back home and that talking to the press would anger immigration authorities.

One woman sat on the floor quietly crying. Poverty had forced her to leave her two sons behind in Honduras, and one had died in her absence. Another mother sat nervously rubbing coins together between her fingers. She left Guatemala with her six-year-old son after her father threatened to hack the family to death with a machete. She told me that most people in custody with her had signed forms in English that they were unable to read, in hopes of being let out of the crowded hielera: “‘What if I never sign, and I’m never let out,’ I thought. I think almost everyone signed. No one knew what those documents said.”

Many parents at the station held yellow envelopes given to them by Catholic Charities that read, “Please help me. I don’t speak English,” while their kids bounced around, dancing and squirming with all the resiliency of childhood. “Dibuje mi mami” one boy commanded. “Draw my mom.”

View Library of 16 photosWant the best of A VICE News straight to your inbox? Sign up here.

A 39-year-old Honduran mother had her 9-year-old child taken from her when she fled to the U.S. to seek asylum. It was three weeks before she was even able to speak to him, and though they were reunited two months later, she experienced depression and post-traumatic stress. She sometimes wondered whether she’d be better off dead.

Physicians for Human Rights has a name for what she endured. They say it’s torture.

“What was a gut-punch for me — as I was reading one report, and another, and another — was the depth of the trauma, the depth of the cruelty of the agents; how they talked to some of the clients, how they misled them, how they lied to them and told them they would never see their children again,” said Dr. Ranit Mishori, co-author of the report and senior medical advisor for Physicians for Human Rights.

The medical evaluations, which took place between July 2018 and August 2019, were part of the migrants’ medical-legal affidavits — a document requested by an attorney to detail the psychological effects of a person’s torture or persecution. The 39-year-old woman, identified only as “Ms. EP” in her medical-legal affidavit, told a social worker in December 2018 that her mind was on “overload” when she was separated from her son, identified as JCP in legal documents. She had taken him with her so he could be safe.

Like many parents separated from their children at the border — either through the Trump administration’s defunct zero tolerance policy or the still-ongoing practice of splitting kids from “unfit” parents — Ms. EP had little control over when she’d see her son again or his care in her absence. The phone number she was given to reach him didn’t work. She was told she’d never see her child again, and worried even once they were reunited that he’d suddenly disappear.

Medical experts have been warning since the Trump administration ramped up family separation in Spring 2018 that the policies could lead to irreparable psychological damage for children and parents, and advocates continue to press that U.S. detention centers are causing families harm.

“Ms. EP reports that she can be hyper vigilant, and often checks to make sure that her son is safe and there is no one around who might take him from her,” a clinical social worker with Physicians for Human Rights Asylum Network wrote in a medical-legal affidavit in December.

“He reports that he does not like to be away from his mother,” the same clinical social worker wrote of her Ms. EP’s son after his December 2018 evaluation. He also struggled to go to the bathroom alone and had trouble sleeping through the night, according to his separate medical-legal affidavit. It was common for separated children to show regressive behaviors like bed-wetting or loss of language, according to the report.

“There was a lot of guilt on many levels; everyone who left left because they thought they were doing the right thing for their child,” said Katherine Peeler, a pediatrician and member of Physicians for Human Rights’ asylum network who conducted evaluations at the Dilley facility. “They wanted to give their child a chance.”

All of the parents interviewed by the medical-advocacy group reported that they came to the U.S. from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras shouldering a good deal of trauma already, only to see that agony and guilt compounded by separation from their children. Fifteen of the 17 adults interviewed had received death threats, for example; 14 reported that they were targeted by gang or cartels. Many had already taken other measures to protect their families before coming to the U.S., like going to local authorities or moving internally within their own country. After those efforts failed, according to the report, they came to the U.S, where they experienced family separation.

“When they’re reunited, it’s not some sort of scene from ‘Love Actually,’ where everyone runs up to each other and is hugging and smiling again,” Peeler said. “There are people who are happy. But for the most part children don’t know what to think, they’re mad at their parents. They think their mother abandoned them or didn’t do enough to stop it. They don’t understand.”

Cover image: A an 8-year-old boy is embraced by a relative after arriving to La Aurora airport in Guatemala City. He stayed in a shelter for migrant children in Houston after his mother Elsa Ortiz Enriquez was deported in June 2018 under President Donald Trump administration's zero tolerance policy. (AP Photo/Oliver de Ros)

Comments

Post a Comment