Between a Rock & a Hard Place: Casino Screwup Royale: A tale of “ethical hacking” gone awry

eBiz & IT / Information Technology Consulting

Between a Rock & a Hard Place: A Casino Screwup Royale - A tale of “Ethical Hacking” Gone Awfully Awry

Certified Information Systems Security Professionals: "C/Ethical Hackers" tried to disclose problems to a casino and its software company — it got messy.

People who find security vulnerabilities commonly run into difficulties when reporting them to the responsible company. But it's less common for such situations to turn into tense trade-show confrontations—and competing claims of assault and blackmail.

Yet that's what happened when executives at Atrient—a casino technology firm headquartered in West Bloomfield, Michigan—stopped responding to two UK-based security researchers who had reported some alleged security flaws. The researchers thought they had reached an agreement regarding payment for their work, but nothing final ever materialized. On February 5, 2019, one of the researchers—Dylan Wheeler, a 23-year-old Australian living in the UK—stopped by Atrient's booth at a London conference to confront the company’s chief operating officer.

What happened next is in dispute. Wheeler says that Atrient COO Jessie Gill got in a confrontation with him and yanked off his conference lanyard; Gill insists he did no such thing, and he accused Wheeler of attempted extortion.

The debacle culminated in legal threats and a lot of mudslinging, with live play-by-play commentary as it played out on Twitter. Rapid7 Director of Research Tod Beardsley was one of the spectators. "My first reaction," Beardsley joked, "was, man, I wish a vendor would punch me for disclosure. Boy, that beats any bug bounty."

— @mikko (@mikko) February 15, 2019

Vulnerability Disclosure Bingo.

From https://t.co/6jvhEvksOe pic.twitter.com/aL0avgSrzq

From https://t.co/6jvhEvksOe pic.twitter.com/aL0avgSrzq

— @mikko (@mikko) February 15, 2019

The story is practically a case study in the problems that can arise with vulnerability research and disclosure.

Many large companies and technology vendors now run active "bug bounty" programs to channel the efforts of outside hackers and security researchers toward productively uncovering security problems in their software and infrastructure—but the vast majority of companies have no clear mechanism for outsiders to share information about security gaps.

When it comes to disclosing vulnerabilities to those types of companies, Beardsley told Ars, "I've gotten everything ranging from silence to active ignorance—'I don't wanna hear it'—to cease and desist letters telling me 'I'll take down your advisory.' All of that, and I've gotten lots of good [responses], too. I've dealt with people who have not had a long track record with disclosure and I hand hold them through it."

In this case, two relatively inexperienced "ethical hackers" tried to feel their way through what they felt was a fairly serious security problem, even as Atrient executives felt like they were being taken for a ride by unscrupulous hackers trying to make a buck. Thanks to call recordings and a months-long e-mail thread between Wheeler, Atrient, and other stakeholders in the disclosure—including a major US casino operator and the FBI's Cyber Division—we have a pretty good idea of how the situation played out.

The company

The company

Atrient's Las Vegas office, just a stone's throw from McCarran International Airport.

Atrient is a small company, plying its wares in a highly specific niche of the casino and gaming industry.

Originally founded in April of 2002 by Sam Attisha and Jashinder (Jessie) Gill as Vistron, Inc. and renamed a year later, according to Michigan corporate records, Atrient was initially a catch-all technology consulting company. It offered "solutions outside the box" (as the company’s original website described them) related to IT staffing, software development, creative services, and project management. The company briefly took a stab at the wireless business, operating Vistron Wireless Inc. to "provide marketing and technology services to the wireless industry," according to corporate registration documents.

Within a few years, Atrient's work grew to include software integration for casinos. By 2015, Atrient’s main focus became a casino customer loyalty system called PowerKiosk, which connects freestanding kiosks, electronic slot machines, and mobile applications to track casino gamblers and present them with rewards, special games and marketing offers. The system can track customers through loyalty cards that it issues or through Bluetooth "beacons" and geolocation using mobile applications, as well as tracking the value of a person's rewards points accumulated by activities within the casino.

While Atrient maintains an office in Las Vegas for sales and customer support, the company's headquarters are in a small office and retail building in West Bloomfield,

Michigan. Atrient's headquarters shares the second floor of the building with a dentist and an H&R Block Advisors office, with a Tim Hortons donut shop and a mattress store below. (Atrient shares its office with Azilen, an IT outsourcing company with two offices in India and one in Belgium. The full relationship between Azilen and Atrient isn't clear; at least one Azilen developer now works for Atrient's subsidiary in Hyderabad, India, which was registered in May of 2018.)

Michigan. Atrient's headquarters shares the second floor of the building with a dentist and an H&R Block Advisors office, with a Tim Hortons donut shop and a mattress store below. (Atrient shares its office with Azilen, an IT outsourcing company with two offices in India and one in Belgium. The full relationship between Azilen and Atrient isn't clear; at least one Azilen developer now works for Atrient's subsidiary in Hyderabad, India, which was registered in May of 2018.)

Atrient has apparently done well in its niche, partnering with a number of major players in the casino and gaming industry. Konami cut a deal in 2014 for exclusive distribution rights to Atrient's software for existing Konami customers. Atrient has also integrated its software with gaming systems from Scientific Games' Bally Technology unit and International Game Technology.

Over the past year or more, Atrient was in negotiations with the gaming and financial tech company Everi Holdings—negotiations that culminated on March 12, 2019 with the announced acquisition of "certain assets and intellectual property" of Atrient by Everi. The $40 million deal was done with $20 million in cash, with additional payouts based on contingencies in the agreement over the next two years. These negotiations were ongoing as the researchers tried to make their security concerns heard.

The researchers

The security researchers in this story have some experience in infosec, but they are not exactly industry veterans. Wheeler is 23, while his partner in the Atrient endeavor was a UK-based 17-year-old identified in e-mails and phone conversations only as Ben. A student studying information technology, Ben goes by @Me9187 or "Me" on Twitter and in other Internet communications.

Wheeler has had more than passing problems with the law in the past—a point Gill was quick to make in responses to Ars immediately following the February 5 incident at the trade show in London. Wheeler once faced hacking charges for activities while he was a minor in Australia, then jumped bail at age 20 to flee to the Czech Republic in order to avoid prosecution. (Wheeler claimed that the case has been closed in Australia and that Australian authorities chose not to pursue him further.) He is now a legal resident in the United Kingdom, where immigration authorities were made aware of his "past criminality," Wheeler said.

"I was 14 when it initiated," Wheeler told Ars, claiming that his case was protected from publication by Australian law (though a number of Australian newspapers have covered the case in detail). "But regardless, the past is over. I’m trying to be as transparent as possible, and I don’t appreciate my past being brought up [by Atrient]. This is the infosec industry... loads of people have backgrounds in this industry."

Shodan Safari

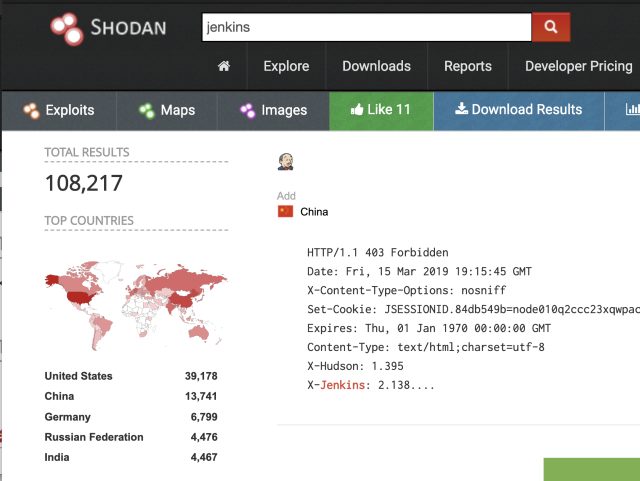

Enlarge / There are over 100,000 Jenkins servers exposed on the Internet, many with security vulnerabilities, that can be located through Shodan.io and Censys.io.

On October 29, 2018, Wheeler and "Me" were engaged in a search for vulnerable systems on the Internet. They sent batches of queries to a pair of Internet vulnerability search engines—Censys and Shodan—via a combination of Web queries and direct commands through the tools' command-line application interfaces. During their search, they stumbled across what amounted to an open door—a Jenkins server they claim had no access controls enabled.

Advertisement

Jenkins, originally a project at Sun Microsystems, is intended to be used as part of a software development pipeline, continuously integrating, compiling, and deploying software builds. But it has had some notable security issues, including past flaws that allowed remote code execution, potentially giving an attacker a foothold within a company’s software supply chain. Wheeler and "Me" claim that the Atrient Jenkins server, running on a Windows instance in the cloud, had no user authentication configured—simply connecting to the server’s Web console gave the pair administrative access. (In a statement, Atrient said that the pair had used a "brute force" attack to gain access.)

Wheeler and "Me" decided to poke around a bit to see if they could identify who owned the server. Using their initial server access to execute two lines of Groovy script, they created a simple remote shell that let them explore the entire server, they said. Based on documents and data found on the server, they believed it was being used by Atrient and employees of Azilen to host development and bug reporting for Atrient's PowerKiosk platform, along with code repositories for mobile applications and kiosk implementations for a number of casinos. They also found a FileZilla File Transfer Protocol server configured on the machine, as well as connections to a number of databases, a repository of source code, and running code serving up Atrient’s PowerKiosk APIs.

Gill insists what the pair found was simply a demonstration platform with no working code. At least one of the "casinos" listed on the server was in fact a demo environment—"Casino Monaco," a fake casino used for trade show demos and Atrient marketing materials.

On November 4, 2018, "Me" and Wheeler sent emails to a host of addresses at Atrient and Azilen—including to CEO Sam Attisha—to alert them to the alleged security problem with the server. "Please forward these details to the relevant security teams and have them contact me," the emails said, providing a list of databases and application programming interfaces (APIs) associated with PowerKiosk, its Web management console, and mobile applications tailored to specific Atrient customers.

It is not unusual for such emails to go unanswered. Full of spelling errors and grammatical mistakes, these emails were not typical "professional" correspondence. (Wheeler says that he was told by Atrient's Attisha that they ended up in his spam folder.)

But Beardsley said that, in his experience, even the most professionally prepared disclosures can be ignored. "We did one on Guardzilla, an all-in-one Wi-Fi home security camera sold at all the big box stores. We could not get anywhere," he said. "We opened up a support ticket, we did some LinkedIn tracking to see who actually worked there, and a journalist even followed up on it and looked up who the agents of the company were, and talked to the registered agent of the company."

Even after all that, the company failed to respond. "It's still unsafe," Beardsley said. "It has unguarded [AWS] S3 [storage] buckets, with all of your home video."

Wheeler didn't go to those lengths. Instead, he and "Me" turned to Twitter in an attempt to get the company's attention. And at this point, Guise Bule got pulled into the disclosure.

Attention achieved

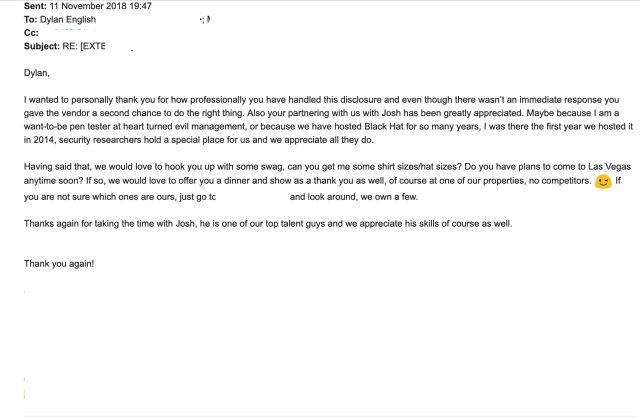

Enlarge / A casino security exec thanks Wheeler and "Me" for their efforts.

A former government security contractor and the co-founder of WebGap, which provides secure, proxied Web browsing, Guise Bule is also the founder of the SecJuice "infosec writers club." Seeking help to get their message amplified, Wheeler and "Me" contacted Bule, who retweeted posts about Atrient. (The tweets have since been deleted.)

Bule’s amplification did help get the attention of two interested parties: a major casino operator that uses Atrient's software—and the FBI.

On November 9, "Me" was contacted by the casino's security team. (Ars attempted to get comments from the casino related to the disclosure; the company did not respond.) On November 10, Wheeler stepped in and sent a summary of what had been found to a security engineer at the casino company:

I’m a colleague of ‘Me’, whom you where [sic] speaking with on Twitter, and subsequently emailed to undertake the contact in this.

The vulernability [sic] per-say is a result of one of your vendors ‘Atrient’, and their poor security protocol, resulting in kiosks treating and moving data unsecurely over HTTP.

Their poor security, which they have not replied to our constant plea to disclose and furthermore patch, has resulted in us going public about our findings, which range from small issues with themselves and their security protocols (I wont [sic] disclose all issues with the company, however a good example would be [your] data held with the vendor, being secured behind a FTP with the username and password being simply the companies name, lowercase.) all the way up to major security issues with their products (PowerKiosk).

The same day, Bule said, he was contacted about his retweet by an FBI agent. Bule then brokered a conference call with Wheeler, "Me," and agents from the FBI’s Cyber Division and Las Vegas field office. Wheeler recorded the call.

Wheeler told the FBI that he and "Me" had no intention of publishing the information they had found, because they were concerned about its severity. It could essentially be used to "print money," Wheeler told the agents. He also shared that he and "Me" had been in touch with the casino operator but had been unable to reach Atrient.

"We might be able to help you with that," one of the FBI agents said.

Wheeler's communications with the casino company were praised by that company's executive director of security in a November 11 email. He wrote to Wheeler, "I wanted to personally thank you for how professionally you have handled this disclosure and event though there wasn't an immediate response you gave the vendor a second chance to do the right thing." He offered to "hook [Wheeler] up with some swag," asking for his shirt and hat sizes.

That same day, the FBI hosted another conference call on the issue—this time bringing in Atrient’s Gill.

During that call, which Wheeler also recorded, Gill said, "The information you’ve shared with us here is fantastic. We’d like to own this information. How do we make that happen?"

Until that moment, money had never entered the conversation. The researchers planned to present their findings at an information security conference at some point, and all Wheeler and "Me" had asked for from the casino operator was some "swag" they could flash whenever they gave their future talk.

But with an NDA on the table, Wheeler brought up the idea of being paid a "bug bounty." He proposed that Atrient pay his company for the equivalent of 140 billable consulting hours—about $60,000.

Check, please

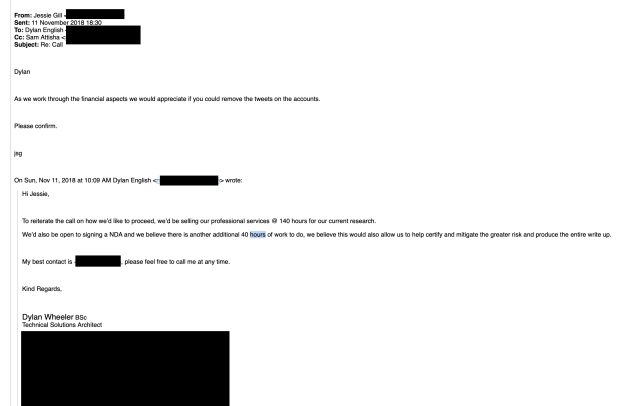

Enlarge / Wheeler reiterates his proposal to bill for 140 hours of consulting time in a follow-up email, while Gill focuses on getting Twitter posts down.

"When you're performing Coordinating Disclosure—calling the vendor for the first time—for me it's super important to really stress, 'Look I'm not trying to sell you anything. I'm not trying to extort you. I'm not trying to set this up as a future sales call for all of my wonderful products,'" said Rapid7's Beardsley. "I am very cognizant of that for a couple reasons. One, I don't want to go to jail. And two, it's an emotional thing for most people, especially people who've never had to deal with [disclosure] before."

Beardsley explained that often, when he's disclosed vulnerabilities, "I am the first security person people have ever talked to outside of their own company." For that reason, he said, "I try to make that as soft touch as I possibly can, and I think that's one of like the skill gaps that we have in IT Security."

But the idea of money was now on the table, and the researchers believed they were going to get paid. The call ended but communications continued. After demanding that "negative tweets toward Atrient" be removed from Me's Twitter account, and after inquiries into the location of the data the pair downloaded from Atrient's server, Gill, Attisha and Atrient's attorney communicated through late 2018 with Wheeler. They told him a draft NDA would be sent to him for review with his lawyer.

Advert

On December 7, 2018, Atrient's attorney emailed Wheeler, saying, "We have a draft ready. Do you want us to send it to your lawyer." Wheeler asked that the draft be sent to him. But no draft appeared.

A week later, Gill told Wheeler in an email that the draft "was delivered to us this week…Sam [Attisha] and I are now reviewing it. We should be able to get it to you Monday [December 17]." There was silence again over the holidays. In an email sent on January 4, 2019, Attisha explained that he and Gill had been traveling.

Weeks went by without additional information. In an email sent on January 21, 2019, Attisha said:

I will be sending over the agreement shortly. We are going to be in London at the end of this month into early February. We could meet and execute the agreement if that works for you."

Wheeler agreed and said he could stop by to meet at the ICE conference in London, since he had registered as an attendee. But as the ICE conference approached, Atrient went silent.

All the while, Atrient was in acquisition negotiations with Everi. At the ICE conference, Everi announced a "partnership" with Atrient, and the two shared expo space to demonstrate their integrated products. Wheeler began to believe that he had simply been put off and would never get paid—and he wanted to confront Atrient execs in person.

Gasoline party

When a company is faced with an unexpected disclosure, founder and CEO of Luta Security Katie Moussouris told Ars, "At a minimum, it's always best to take the high road." Companies can do that by creating or clarifying their policy around vulnerability disclosure and by limiting public comments to a "holding statement" indicating that the company is working to resolve the issue.

"Nothing else really 'wins' in the court of public opinion," Moussouris explained. "The bigger the organization, the higher the road they must take, or they will come off as a bully." As for the researchers, Moussouris said, "It's a lot easier to both protect yourself legally and in public discourse the more professional you are."

That is not the route anyone took in this case.

With a friend in tow, Wheeler visited Atrient's joint booth with Everi at the ICE conference on February 5. There he saw Gill, and a confrontation ensued. Wheeler claims Gill made some reference to Wheeler's "friends."

Wheeler promptly posted a video of him accusing Gill of assault—though the video itself showed no assault. Gill denied it.

In emails to Wheeler and in a later phone interview with Ars, Gill accused Wheeler of being part of a conspiracy to extort Atrient. Gill soon sent Wheeler, "Me," and Bule the following email:

We write further to your email of earlier today and following your co-conspirator's appearance at our company stand at the ICE trade fair in London making certain statements regarding the security of our systems.

You and your colleagues were responsible for unauthorized hacking of our demo platform in November 2018 and as a result, came into the possession of certain proprietary information of ours and our customers’ (the “Confidential Information”). You and your co-conspirators demanded money from us in return of the Confidential Information. We are not prepared to recompense you for carrying out illegal activities AND DO NOT RESPOND TO THREATS.

As you are aware we contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation regarding your illegal activities in November last year and are now in contact with the relevant authorities in the United Kingdom, Europe and Australia.

We require you to immediately:

Cease all further threats to us and our employees, representatives, customers and advisers;

Return all copies of the Confidential Information in your possession or control;

Identify where any of the Confidential Information is stored in an electronic format, whether stored on a device or storage medium in your possession or control, or on a remote server or cloud storage facility, take all steps necessary to ensure that the electronic storage of that Confidential Information is completely and irrevocably erased and destroyed, including all copies and backups, and any transitory or temporary copies made, such that no person, can access the Confidential Information, or any information contained therein.

You must not publish any of the Confidential Information or any information in relation to the unauthorized hacking or otherwise make any such Confidential Information or information available to the public.

Please confirm by return and by no later than 9am UK time tomorrow morning that you have and will comply with the contents of this communication.

We are taking legal advice in respect of the actions we are entitled to pursue against you and your co-conspirators in both civil and criminal proceedings. In the meantime reserve all of our rights in this regard.

What you may feel has an impact on Atrient or our clients are based on fiction.

Atrient quickly published a statement on its Twitter account about the convention incident—and then removed the statement. (Gill said this was done "for formatting.") Another version of the statement was then emailed to Ars and to other press outlets by a UK public relations firm. It read:

We have become aware of false claims regarding a security vulnerability relating to one of our products and an alleged assault.

In November 2018, one of our product sales websites was subject to a brute force attack on a demo server which contained no personal data. The extent of the attack identified demo sites that our sales department engaged.

We were subsequently contacted by a group. This included an individual who identified himself as Dylan English, which we now know to be an alias, Guise Bule of secjuice.com, and an individual who refused to identify himself by a name. Shortly after being contacted, it became apparent that there was a financial motive for not publicising the allegations. The FBI is aware of this group.

On 6 February 2019 we received an unscheduled visit to the Atrient stand at the ICE conference in London from one of the ‘security researchers’. He was wearing a badge which identified him as Dylan Wheeler, which we believe to be his real name. After being informed that Atrient would not pay any money he made another false accusation, this time of assault, which an ExCel Convention Centre investigation has found to be baseless.

This matter is now in the hands of the company’s legal advisers and law enforcement. It would therefore not be appropriate to comment any further.

Wheeler's email address does show his name as "Dylan English"—the trade name he uses for his information security firm work. But his emails to Atrient, the casino operator, and the FBI each included his full name in the signature, so his real name should have been known to all participants.

After this response from Atrient, Wheeler sent emails to the FBI agents and to the casino operator, telling them he had been assaulted—and that Atrient had not bothered to fix the vulnerability. He then gave the whole story to Bule, along with links to the recorded FBI conference calls and screen shots, to publish on SecJuice. The details of the security issues Wheeler and "Me" brought to Atrient are now a matter of public record.

Know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em

Nothing about the way the situation unraveled is surprising to Beardsley. "People who are in the vulnerability disclosure business learn this really quickly—the fact is people don't generally do this very often, and so we're all bad at it," he said. "We don't have good practices."

Even when coordinated disclosure goes well—without NDAs, legal threats, and whatnot—it can take months. But the upside of doing it right, Beardsley said, is "then maybe the company will respond better to the next guy who comes along with a disclosure, and maybe doesn't have as light a touch as you. That's all you can kind of hope for."

The interaction between Wheeler and the casino operator is an example of how disclosure can be handled well—and it went well because the casino had a security team ready and willing to respond. It also helped that money never entered the discussion.

But the animus between Atrient and the researchers seems to have been about more than money. There was also the timing of the disclosure, with a $40 million deal close to its conclusion when the report came in. Given the business situation, the relatively short timeframe (by disclosure standards), and the way the conversation took place, it's not surprising that emotions ran high on Atrient's side. Fireworks were almost inevitable.

Veterans of disclosure, Beardsley said, "know this is all normal, and we can expect what we expect, but someone who doesn't have a lot of experience can get emotional and personal about it and all that. It's on us as an industry not only to train corporate America on how to take disclosure, but also we need to do a little more training for people who find these bugs—especially today, in an era where bug outings are kind of normal now—to not expect someone to be necessarily grateful when one shows up."

The researchers

The security researchers in this story have some experience in infosec, but they are not exactly industry veterans. Wheeler is 23, while his partner in the Atrient endeavor was a UK-based 17-year-old identified in e-mails and phone conversations only as Ben. A student studying information technology, Ben goes by @Me9187 or "Me" on Twitter and in other Internet communications.

Wheeler has had more than passing problems with the law in the past—a point Gill was quick to make in responses to Ars immediately following the February 5 incident at the trade show in London. Wheeler once faced hacking charges for activities while he was a minor in Australia, then jumped bail at age 20 to flee to the Czech Republic in order to avoid prosecution. (Wheeler claimed that the case has been closed in Australia and that Australian authorities chose not to pursue him further.) He is now a legal resident in the United Kingdom, where immigration authorities were made aware of his "past criminality," Wheeler said.

"I was 14 when it initiated," Wheeler told Ars, claiming that his case was protected from publication by Australian law (though a number of Australian newspapers have covered the case in detail). "But regardless, the past is over. I’m trying to be as transparent as possible, and I don’t appreciate my past being brought up [by Atrient]. This is the infosec industry... loads of people have backgrounds in this industry."

Shodan Safari

Enlarge / There are over 100,000 Jenkins servers exposed on the Internet, many with security vulnerabilities, that can be located through Shodan.io and Censys.io.

On October 29, 2018, Wheeler and "Me" were engaged in a search for vulnerable systems on the Internet. They sent batches of queries to a pair of Internet vulnerability search engines—Censys and Shodan—via a combination of Web queries and direct commands through the tools' command-line application interfaces. During their search, they stumbled across what amounted to an open door—a Jenkins server they claim had no access controls enabled.

Advertisement

Jenkins, originally a project at Sun Microsystems, is intended to be used as part of a software development pipeline, continuously integrating, compiling, and deploying software builds. But it has had some notable security issues, including past flaws that allowed remote code execution, potentially giving an attacker a foothold within a company’s software supply chain. Wheeler and "Me" claim that the Atrient Jenkins server, running on a Windows instance in the cloud, had no user authentication configured—simply connecting to the server’s Web console gave the pair administrative access. (In a statement, Atrient said that the pair had used a "brute force" attack to gain access.)

Wheeler and "Me" decided to poke around a bit to see if they could identify who owned the server. Using their initial server access to execute two lines of Groovy script, they created a simple remote shell that let them explore the entire server, they said. Based on documents and data found on the server, they believed it was being used by Atrient and employees of Azilen to host development and bug reporting for Atrient's PowerKiosk platform, along with code repositories for mobile applications and kiosk implementations for a number of casinos. They also found a FileZilla File Transfer Protocol server configured on the machine, as well as connections to a number of databases, a repository of source code, and running code serving up Atrient’s PowerKiosk APIs.

Gill insists what the pair found was simply a demonstration platform with no working code. At least one of the "casinos" listed on the server was in fact a demo environment—"Casino Monaco," a fake casino used for trade show demos and Atrient marketing materials.

On November 4, 2018, "Me" and Wheeler sent emails to a host of addresses at Atrient and Azilen—including to CEO Sam Attisha—to alert them to the alleged security problem with the server. "Please forward these details to the relevant security teams and have them contact me," the emails said, providing a list of databases and application programming interfaces (APIs) associated with PowerKiosk, its Web management console, and mobile applications tailored to specific Atrient customers.

It is not unusual for such emails to go unanswered. Full of spelling errors and grammatical mistakes, these emails were not typical "professional" correspondence. (Wheeler says that he was told by Atrient's Attisha that they ended up in his spam folder.)

But Beardsley said that, in his experience, even the most professionally prepared disclosures can be ignored. "We did one on Guardzilla, an all-in-one Wi-Fi home security camera sold at all the big box stores. We could not get anywhere," he said. "We opened up a support ticket, we did some LinkedIn tracking to see who actually worked there, and a journalist even followed up on it and looked up who the agents of the company were, and talked to the registered agent of the company."

Even after all that, the company failed to respond. "It's still unsafe," Beardsley said. "It has unguarded [AWS] S3 [storage] buckets, with all of your home video."

Wheeler didn't go to those lengths. Instead, he and "Me" turned to Twitter in an attempt to get the company's attention. And at this point, Guise Bule got pulled into the disclosure.

Attention achieved

Enlarge / A casino security exec thanks Wheeler and "Me" for their efforts.

A former government security contractor and the co-founder of WebGap, which provides secure, proxied Web browsing, Guise Bule is also the founder of the SecJuice "infosec writers club." Seeking help to get their message amplified, Wheeler and "Me" contacted Bule, who retweeted posts about Atrient. (The tweets have since been deleted.)

Bule’s amplification did help get the attention of two interested parties: a major casino operator that uses Atrient's software—and the FBI.

On November 9, "Me" was contacted by the casino's security team. (Ars attempted to get comments from the casino related to the disclosure; the company did not respond.) On November 10, Wheeler stepped in and sent a summary of what had been found to a security engineer at the casino company:

I’m a colleague of ‘Me’, whom you where [sic] speaking with on Twitter, and subsequently emailed to undertake the contact in this.

The vulernability [sic] per-say is a result of one of your vendors ‘Atrient’, and their poor security protocol, resulting in kiosks treating and moving data unsecurely over HTTP.

Their poor security, which they have not replied to our constant plea to disclose and furthermore patch, has resulted in us going public about our findings, which range from small issues with themselves and their security protocols (I wont [sic] disclose all issues with the company, however a good example would be [your] data held with the vendor, being secured behind a FTP with the username and password being simply the companies name, lowercase.) all the way up to major security issues with their products (PowerKiosk).

The same day, Bule said, he was contacted about his retweet by an FBI agent. Bule then brokered a conference call with Wheeler, "Me," and agents from the FBI’s Cyber Division and Las Vegas field office. Wheeler recorded the call.

Wheeler told the FBI that he and "Me" had no intention of publishing the information they had found, because they were concerned about its severity. It could essentially be used to "print money," Wheeler told the agents. He also shared that he and "Me" had been in touch with the casino operator but had been unable to reach Atrient.

"We might be able to help you with that," one of the FBI agents said.

Wheeler's communications with the casino company were praised by that company's executive director of security in a November 11 email. He wrote to Wheeler, "I wanted to personally thank you for how professionally you have handled this disclosure and event though there wasn't an immediate response you gave the vendor a second chance to do the right thing." He offered to "hook [Wheeler] up with some swag," asking for his shirt and hat sizes.

That same day, the FBI hosted another conference call on the issue—this time bringing in Atrient’s Gill.

During that call, which Wheeler also recorded, Gill said, "The information you’ve shared with us here is fantastic. We’d like to own this information. How do we make that happen?"

Until that moment, money had never entered the conversation. The researchers planned to present their findings at an information security conference at some point, and all Wheeler and "Me" had asked for from the casino operator was some "swag" they could flash whenever they gave their future talk.

But with an NDA on the table, Wheeler brought up the idea of being paid a "bug bounty." He proposed that Atrient pay his company for the equivalent of 140 billable consulting hours—about $60,000.

Check, please

Enlarge / Wheeler reiterates his proposal to bill for 140 hours of consulting time in a follow-up email, while Gill focuses on getting Twitter posts down.

"When you're performing Coordinating Disclosure—calling the vendor for the first time—for me it's super important to really stress, 'Look I'm not trying to sell you anything. I'm not trying to extort you. I'm not trying to set this up as a future sales call for all of my wonderful products,'" said Rapid7's Beardsley. "I am very cognizant of that for a couple reasons. One, I don't want to go to jail. And two, it's an emotional thing for most people, especially people who've never had to deal with [disclosure] before."

Beardsley explained that often, when he's disclosed vulnerabilities, "I am the first security person people have ever talked to outside of their own company." For that reason, he said, "I try to make that as soft touch as I possibly can, and I think that's one of like the skill gaps that we have in IT Security."

But the idea of money was now on the table, and the researchers believed they were going to get paid. The call ended but communications continued. After demanding that "negative tweets toward Atrient" be removed from Me's Twitter account, and after inquiries into the location of the data the pair downloaded from Atrient's server, Gill, Attisha and Atrient's attorney communicated through late 2018 with Wheeler. They told him a draft NDA would be sent to him for review with his lawyer.

Advert

On December 7, 2018, Atrient's attorney emailed Wheeler, saying, "We have a draft ready. Do you want us to send it to your lawyer." Wheeler asked that the draft be sent to him. But no draft appeared.

A week later, Gill told Wheeler in an email that the draft "was delivered to us this week…Sam [Attisha] and I are now reviewing it. We should be able to get it to you Monday [December 17]." There was silence again over the holidays. In an email sent on January 4, 2019, Attisha explained that he and Gill had been traveling.

Weeks went by without additional information. In an email sent on January 21, 2019, Attisha said:

I will be sending over the agreement shortly. We are going to be in London at the end of this month into early February. We could meet and execute the agreement if that works for you."

Wheeler agreed and said he could stop by to meet at the ICE conference in London, since he had registered as an attendee. But as the ICE conference approached, Atrient went silent.

All the while, Atrient was in acquisition negotiations with Everi. At the ICE conference, Everi announced a "partnership" with Atrient, and the two shared expo space to demonstrate their integrated products. Wheeler began to believe that he had simply been put off and would never get paid—and he wanted to confront Atrient execs in person.

Gasoline party

When a company is faced with an unexpected disclosure, founder and CEO of Luta Security Katie Moussouris told Ars, "At a minimum, it's always best to take the high road." Companies can do that by creating or clarifying their policy around vulnerability disclosure and by limiting public comments to a "holding statement" indicating that the company is working to resolve the issue.

"Nothing else really 'wins' in the court of public opinion," Moussouris explained. "The bigger the organization, the higher the road they must take, or they will come off as a bully." As for the researchers, Moussouris said, "It's a lot easier to both protect yourself legally and in public discourse the more professional you are."

That is not the route anyone took in this case.

With a friend in tow, Wheeler visited Atrient's joint booth with Everi at the ICE conference on February 5. There he saw Gill, and a confrontation ensued. Wheeler claims Gill made some reference to Wheeler's "friends."

Wheeler promptly posted a video of him accusing Gill of assault—though the video itself showed no assault. Gill denied it.

In emails to Wheeler and in a later phone interview with Ars, Gill accused Wheeler of being part of a conspiracy to extort Atrient. Gill soon sent Wheeler, "Me," and Bule the following email:

We write further to your email of earlier today and following your co-conspirator's appearance at our company stand at the ICE trade fair in London making certain statements regarding the security of our systems.

You and your colleagues were responsible for unauthorized hacking of our demo platform in November 2018 and as a result, came into the possession of certain proprietary information of ours and our customers’ (the “Confidential Information”). You and your co-conspirators demanded money from us in return of the Confidential Information. We are not prepared to recompense you for carrying out illegal activities AND DO NOT RESPOND TO THREATS.

As you are aware we contacted the Federal Bureau of Investigation regarding your illegal activities in November last year and are now in contact with the relevant authorities in the United Kingdom, Europe and Australia.

We require you to immediately:

Cease all further threats to us and our employees, representatives, customers and advisers;

Return all copies of the Confidential Information in your possession or control;

Identify where any of the Confidential Information is stored in an electronic format, whether stored on a device or storage medium in your possession or control, or on a remote server or cloud storage facility, take all steps necessary to ensure that the electronic storage of that Confidential Information is completely and irrevocably erased and destroyed, including all copies and backups, and any transitory or temporary copies made, such that no person, can access the Confidential Information, or any information contained therein.

You must not publish any of the Confidential Information or any information in relation to the unauthorized hacking or otherwise make any such Confidential Information or information available to the public.

Please confirm by return and by no later than 9am UK time tomorrow morning that you have and will comply with the contents of this communication.

We are taking legal advice in respect of the actions we are entitled to pursue against you and your co-conspirators in both civil and criminal proceedings. In the meantime reserve all of our rights in this regard.

What you may feel has an impact on Atrient or our clients are based on fiction.

Atrient quickly published a statement on its Twitter account about the convention incident—and then removed the statement. (Gill said this was done "for formatting.") Another version of the statement was then emailed to Ars and to other press outlets by a UK public relations firm. It read:

We have become aware of false claims regarding a security vulnerability relating to one of our products and an alleged assault.

In November 2018, one of our product sales websites was subject to a brute force attack on a demo server which contained no personal data. The extent of the attack identified demo sites that our sales department engaged.

We were subsequently contacted by a group. This included an individual who identified himself as Dylan English, which we now know to be an alias, Guise Bule of secjuice.com, and an individual who refused to identify himself by a name. Shortly after being contacted, it became apparent that there was a financial motive for not publicising the allegations. The FBI is aware of this group.

On 6 February 2019 we received an unscheduled visit to the Atrient stand at the ICE conference in London from one of the ‘security researchers’. He was wearing a badge which identified him as Dylan Wheeler, which we believe to be his real name. After being informed that Atrient would not pay any money he made another false accusation, this time of assault, which an ExCel Convention Centre investigation has found to be baseless.

This matter is now in the hands of the company’s legal advisers and law enforcement. It would therefore not be appropriate to comment any further.

Wheeler's email address does show his name as "Dylan English"—the trade name he uses for his information security firm work. But his emails to Atrient, the casino operator, and the FBI each included his full name in the signature, so his real name should have been known to all participants.

After this response from Atrient, Wheeler sent emails to the FBI agents and to the casino operator, telling them he had been assaulted—and that Atrient had not bothered to fix the vulnerability. He then gave the whole story to Bule, along with links to the recorded FBI conference calls and screen shots, to publish on SecJuice. The details of the security issues Wheeler and "Me" brought to Atrient are now a matter of public record.

Know when to hold 'em, know when to fold 'em

Nothing about the way the situation unraveled is surprising to Beardsley. "People who are in the vulnerability disclosure business learn this really quickly—the fact is people don't generally do this very often, and so we're all bad at it," he said. "We don't have good practices."

Even when coordinated disclosure goes well—without NDAs, legal threats, and whatnot—it can take months. But the upside of doing it right, Beardsley said, is "then maybe the company will respond better to the next guy who comes along with a disclosure, and maybe doesn't have as light a touch as you. That's all you can kind of hope for."

The interaction between Wheeler and the casino operator is an example of how disclosure can be handled well—and it went well because the casino had a security team ready and willing to respond. It also helped that money never entered the discussion.

But the animus between Atrient and the researchers seems to have been about more than money. There was also the timing of the disclosure, with a $40 million deal close to its conclusion when the report came in. Given the business situation, the relatively short timeframe (by disclosure standards), and the way the conversation took place, it's not surprising that emotions ran high on Atrient's side. Fireworks were almost inevitable.

Veterans of disclosure, Beardsley said, "know this is all normal, and we can expect what we expect, but someone who doesn't have a lot of experience can get emotional and personal about it and all that. It's on us as an industry not only to train corporate America on how to take disclosure, but also we need to do a little more training for people who find these bugs—especially today, in an era where bug outings are kind of normal now—to not expect someone to be necessarily grateful when one shows up."

Comments

Post a Comment