What's so hard about taking CTA action?

Such strategies, it turns out, may be psychologically sound and cognitively fruitful. In the altogether illuminating 1994 volume Psychology of Writing (public library), cognitive psychologist Ronald T. Kellogg explores how work schedules, behavioral rituals, to the point of being almost compulsive and writing environments affect the amount of time invested in trying to write and the degree to which that time is spent in a state of boredom, aprehensión, anxiety, or creative flow. Kellogg writes:

[There is] evidence that environments, schedules, and rituals restructure the writing process and amplify performance… The principles of memory retrieval suggest that certain practices should amplify performance. These practices encourage a state of flow rather than one of aprehensión, anxiety or boredom. Like strategies, these other aspects of a writer’s method may alleviate the difficulty of attentional overload. The room, time of day, or ritual selected for working may enable or even induce intense concentration or a favorable motivational or emotional state. Moreover, in accordance with encoding specificity, each of these aspects of method may trigger retrieval of ideas, facts, plans, and other relevant knowledge associated with the place, time, or frame of mind selected by the writer for work.

Kellogg reviews a vast body of research to extract a few notable nuggets or findings. Among them is the role of background noise, which seems to fall on a bell curve of fecundity: High-intensity noise that exceeds 95 decibels disrupts performance on complex tasks but improves it on simple, boring tasks — noise tends to raise arousal level, which can be useful when trying to stay alert during mindless and monotonous work, but can agitate you out of creative flow when immersed in the kind of work that requires deliberate, reflective thought. (The psychology of writing, after all, as Kellogg notes in the introduction, is a proxy for the psychology of thinking.) The correlation between skill level and task difficulty also plays a role — feeling like your skills are not up to par raises your level of anxiety, which in turn makes noise more bothersome.

These effects, of course, are relative to one’s psychological constitution — Kellogg surmises that writers more afflicted with the modern epidemic of aprehension & anxiety tend to be more disconcerted by noisy environments. Proust and Carlyle appear to have been among those writers — the former wrote in a cork-lined room to eliminate obtrusive sounds and the latter in a noiseproof chamber to ensure absolute silence — whereas Allen Ginsberg was known for being able to write anywhere, from trains to planes to parks. What matters, Kellogg points out, are each writer’s highly subjective requirements for preserving the state of flow:

The lack of interruption in trains of thought may be the critical ingredient in an environment that enables creative flow. As long as a writer can tune out background noise, the decibel level per se may be unimportant. For some writers, the dripping of a faucet may be more disruptive than the bustle of a cafe in the heart of a city.

Turning an eye to research on the specific timing and duration of writing sessions, Kellogg points to several studies indicating that working for 1 to 3 hours at a time, then taking a break before resuming, is most conducive to productivity, not only for writers but also for athletes and professional musicians etc. — a finding since repeated in more recent research. He also cites a 1985 study of circadian rhythms — something scientists have since explored with swelling rigor — which found that performance on intellectual tasks peaks during morning hours, whereas perceptual-motor tasks fare better in the afternoon and evening. Hemingway, in fact, intuited this from his own experience, telling George Plimpton in a rare 1958 interview:

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until morning when you hit it again. You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that.

Location and physical environment also play a role in maintaining a sustained and productive workflow. Bob Dylan, for instance, extolled the virtues of being able to “put yourself in an environment where you can completely accept all the unconscious stuff that comes to you from your inner workings of your mind - stream of consciousness.” Reviewing the research, Kellogg echoes Faulkner’s memorable assertion that “the only environment the artist needs is whatever peace, whatever solitude, and whatever pleasure he can get at not too high a cost, by being alone” and notes that writers’ dedicated workspaces tend to involve solitude and quiet, although “during the apprenticeship phase of a writer’s career, almost any environment is workable” — most likely a hybrid function of youth’s high tolerance for distraction and the necessity of sharing space earlier in life when the luxury of privacy is unaffordable.

But the key psychological function of such dedicated environments isn’t so much superstitious ritualization — an effort to summon the muse through the elaborate juju of putting everything in its right place — as cognitive cueing. Kellogg considers the usefulness of a special space used solely for writing, which cultivates an “environment that cues the desired behavior”:

This phenomenon can be reinterpreted in terms of the cognitive concept of encoding specificity. The abstract ideas, images, plans, tentative sentences, feelings, and other personal symbols that represent the knowledge needed to construct a text are associated with the place and time of the writing environment. These associations are strongest when the writer engages in few if any extraneous activities in the selected environment. Entering the environment serves as a retrieval cue for the relevant knowledge to enter the writer’s awareness. Once the writer’s attention turns to the ideas that pop into consciousness, the composing process flows again. Particular features of the environment may serve as specific prompts for retrieving, creating, and thinking.

For instance, a scene outside an office window, a painting hanging on the wall, or a plant sitting in the corner may become associated with thinking deeply about a particular text under development. Staring at the feature elicits knowledge representations bearing on the problem at hand.

This strategy is rather similar to the one most often recommended for treating insomnia — instituting a regular bedtime and using the bedroom as a space dedicated solely to sleep, in order to optimize the brain’s ability to enter rest mode upon going to bed and cue that behavior each night just by entering that environment. (Perhaps not coincidentally, many of the most successful writers are also zealous in their sleep habits.)

In fact, Kellogg cites a 1990 treatment program, developed by research psychologist Bob Boice developed for educators and other professionals who must write for a living and who were struggling with writer’s block, which uses a similar approach:

A key component of [Boice’s] program is the rearranging of the writing environment. He recommends that the writer “establish one or a few regular places in which you do all serious writing” and “nothing but serious writing; other writing (e.g., correspondence) would be carried out elsewhere.” Boice insists that magazines, novels, and other nonessential reading material be banned, social interactions minimized or eliminated, and cleaning and straightening up of the place delayed until a writing session is completed. By following these recommendations, the writer creates a space solely to think and write, avoiding extraneous activities. This space, therefore, becomes associated with all the mental products of creating meaning and can then serve as a unique retrieval cue for those products.

Note that these strategies were developed more than a decade before modern smartphones existed and long before social networks like Facebook and Twitter were moaning their constant 95-decibel siren calls for our attention. Today, Boice’s treatment program would no doubt also require the elimination of smartphones and any medium of social networking from the dedicated writing environment, among countless other “nonessential” forms of communication that the past, as is usually the case, could not have envisioned of the future.

Thomas Mann seems to have captured many of the principles Kellogg unveils in a single exquisite letter to the Austrian writer and journalist Viktor Polzer:

For writing I must have a roof over my head, and since I enjoy working by the sea better than anywhere else, I need a tent or a wicker beach chair. Much of my composition, as I have said, has been conceived on walks; I also regard movement in the open air as the best means of reviving my energy for work. For a longer book I usually have a heap of preliminary papers close at hand during the writing; scribbled notes, memory props, in part purely objective — external details, colorful odds and ends — or else psychological formulations, fragmentary inspirations, which I use in their proper place.

In the closing of the chapter, Kellogg considers what the wide variation of such routines and rituals reveals:

The diversity in environments chosen by writers, from Proust’s cork-lined room to Sarraute’s Parisian cafe, suggests the flexibility of human thought. A person can think in any environment, though some locations become habitual for certain individuals. The key is to find an environment that allows concentrated absorption in the task and maximum exposure to retrieval cues that release relevant knowledge from long-term memory.

Indeed, despite all these fruitful strategies for optimizing creative flow, the bigger truth — something I wholeheartedly believe — remains: There is no ideal rotation of the chair or perfect position of the desk clock that guarantees a Pulitzer. What counts, ultimately, is putting your backside in the chair — or, if you happen to be Ernest Hemingway or Virginia Woolf, dragging your feet to your standing desk — and clocking in the hours, psychoemotional rain or shine. Showing up day in and day out, without fail, is the surest way to achieve lasting success.

Complement The Psychology of Writing — which goes on to explore such cognitive crannies as the intricacies of symbol-creation, the role of personality in writing, and the impact of drugs and daydreams on the creative process — with Anna Deavere Smith on discipline, a guided tour of the daily rituals of famous writers, and some pointers on how to hone your creative routine.

You’re supposed to write an essay, whitepaper or a blog post but you procrastinate. The treadmill is collecting dust in your basement. You want to learn a language, start a business or change careers, but those ideas go nowhere. Inaction is something we’ve all experienced. A default decisión is being made herein.

Inaction, more than anything else, is the cause of our failures and our miseries. If we could consistently do the things we know we ought to, life would be much easier. Your projects would be more successful. Your goals & objectives would become a reality. Your life could be better.

We all know action is hard. But why? Why do we struggle so much to take action?

It’s easy to simply take this for granted, to assume laziness is just an intrinsic feature of the human psyche. But it’s also possible to imagine an alternative where action happened without so much inner struggle.

Indeed, you don’t even have to imagine a hypothetical universe to consider this possibility, because there are people who exist in our world who seem to be extraordinarily good at taking action. Arnold Schwarzenegger moving to America, becoming a famous bodybuilder, actor, entrepreneur, then politician. Elon Musk starting PayPal, Nikola, Tesla, SpaceX, Boring and more. Marie Curie winning two Nobel prizes while raising a family as a widowed mother.

There seems to be an amazingly high correlation between the ability to take action and eventual success. Action and success are so closely matched, that it makes the struggles we have with inaction all the more perplexing. If success in life is often as simple as “do things, learn from them, repeat” why do many of us get caught in loops of laziness, self-sabotage and procrastination?

Some Possible Explanations for the Difficulty of Doing

There’s a lot of possible reasons why action is hard. Before I try to offer some explanations, however, I want to look at some theories that don’t do the job very well:

- Talent. Talent, intelligence and serendipity are multipliers of your ability to execute. Obviously, Marie Curie was brilliant. That brilliance, combined with picking just-the-right research project, contributed to her discovering radium and making history. But while talent is obviously an ingredient in success, it doesn’t seem to be all that correlated with taking action. The world is populated by brilliant stars that flame out and mediocre minds that build empires.

- Preferences. I have no desire for Elon Musk’s working life. I’m okay with the fact that this means I probably won’t have a similar level of impact on the world. That’s a difference in preferences, which likely explains part of the range we see in how much people are willing to work hard. But preferences can’t explain why we struggle with ourselves so much. Why procrastinate forever on an essay you know you’ll do eventually? Why start learning the language for weeks if you know you’ll never get to a level where you can use it? Preferences can explain failing to try, but they don’t work well to explain our inner struggles with inaction.

- Capacity for effort. Perhaps effort is simply a different kind of talent, different from intelligence. Have a large capacity and you can easily do a lot of things. Have a low capacity and everything is a struggle. While this explanation does seem partly true, it doesn’t match the pattern of struggle we experience. If your capacity for effort is lower, why wouldn’t this just slow you down, rather than have you experience chronic bursts of activity with inevitable crashes in your goals and projects?

- Motivation. Many of the people who have the hardest time taking action have the most reason to change. Someone leading a grossly unhealthy lifestyle will benefit the most from a small intervention, compared to the hyper-fit trying to lower bodyfat percentage by another 1%. If you define motivation as objectively having a good reason to act, then there’s still a big gap in action that needs explaining. If, instead, you define motivation as a subjective feeling, then we’re simply back to our original puzzle: why do some people feel motivated to do the things they should while others don’t?

My own thinking about the exact causes of inaction aren’t fully developed yet, but I want to try to flesh out some possibilities here, as well as give myself some directions for digging in further.

Possibility #1: Confidence

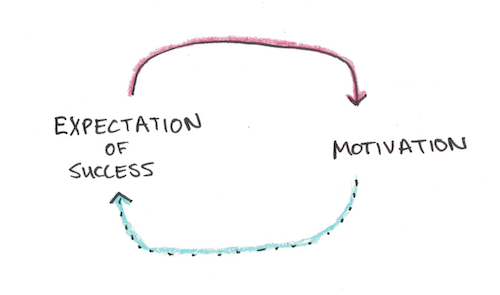

A popular class of theories related to goal-setting are those known as expectancy theories. These are essentially theories that say your motivation to complete a task depends both on the value of the reward you anticipate receiving, as well as your expectation that you’ll actually get that reward.

Your expectations of success, however, also depends on your motivation. This creates a feedback loop where your own expectation of your ability to sustain motivation long-term influences your expectation of success, thus influencing your motivation long-term.

A positive feedback loop can create a system where there are two possible dynamics: an accelerating commitment as you think success is more and more likely, and thus get more and more motivated, as well as a spiral of lowered expectations as you get increasingly discouraged.

Since your expectations of one pursuit often influence future pursuits, this is also something that might stabilize into a general response of doing or inaction in your life. If your projects tend to fail, your expectations are low and motivation withers. If your projects tend to succeed, your expectations go up and motivation stays strong.

Possibility #2: Social-Desirability Bias

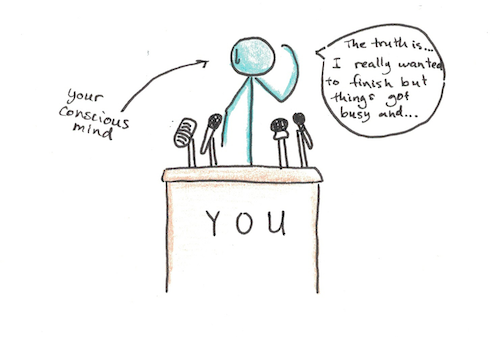

One view of the conscious mind is that it functions more as the brain’s public relations manager than as its CEO, confabulating reasonable-sounding explanations for its behavior rather than actually calling the shots.

If so, this suggests that many of our failures of action are intentional. We fail to take action because the unconscious parts of our mind that drive our behavior have decided not to take action.

Where this gets interesting as a possible explanation, however, is that sometimes inaction isn’t socially acceptable. Thus, we need to feign taking action in order to suggest to others that we do care, even when we don’t. This pretending may even be completely unconscious. The easiest way to lie is to believe you’re telling the truth, so you may even convince yourself you want to pursue a goal when really your unconscious mind is not committed to it.

This might manifest itself in the student who procrastinates on his homework (but doesn’t know why) because he doesn’t really want to study, but has to get the approval and financial support of his parents. Inner friction and anguish may be the price he pays for needing to appear like he’s trying to take action.

Possibility #3: Daydreams Feel Different From Reality

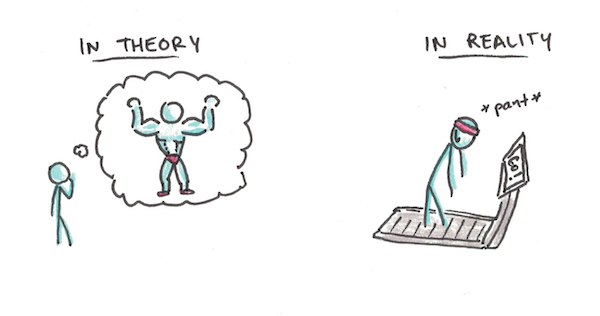

Construal level theory is the idea that we have two characteristic modes of viewing things—an abstract (or far-mode) and a concrete (or near-mode) view.

Many big goals have a far-near incompatibility which can make them hard to take action on. You might think about your fitness goal in terms of losing weight, being healthy and looking great (all abstract, idealized goals). Yet, when you go to the gym you mostly think about how hard you’re breathing, the sweat dripping down your face and how uncomfortable it makes you.

Chronic issues of starting and stopping difficult projects likely depend on this incompatibility of mental states. The person who dreams up the goal is different from the person who executes on it, and coordinating those two versions of yourself may be hard.

Possibility #4: Don’t Stick Your Neck Out

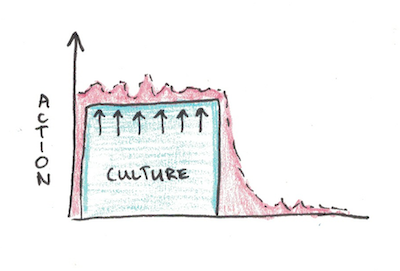

It may be that our hardwiring for ambition itself is based on our environment. Many of our ancestors lived in times when standing out, taking actions that go beyond cultural expectations could get you killed or exiled. Our natures, then, may be trying to sniff out the cost-benefits of taking actions, willing to retreat to placid conformity in case those early ventures get punished.

This might make for a theory of motivation that says, “do whatever your culture requires you to do,” with ventures into different kinds of actions being strongly discouraged if they don’t yield big rewards.

This may also explain why inaction seems to happen with some areas of life (starting your own business), but not others (showing up to work on time). In the second case, there’s a strong cultural expectation that everybody needs to show up on time to work, whereas nobody will blame you for not starting a company.

Our inner struggles may be our unconscious minds trying to find the frontier of action-taking that we’re best suited for, adjusting our ambitions and overall tendency to act based on feedback from the environment.

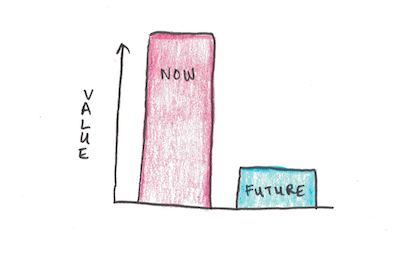

Possibility #5: We’re Too Short-Sighted

It may also be simply that our modern environment, which is peaceful, stable and allows for long-term accumulation of skills and resources, is quite different from the one we’ve evolved to survive in.

In particular, human beings exhibit inconsistent time preferences for satisfaction here and now, versus long-term rewards in the future. Procrastination may be a delaying tactic to avoid wasting energy here and now, even if you think you might work harder in the not-so-far future.

The ability to accumulate resources likely only started after the Neolithic revolution, where grain agriculture allowed some to save (and steal) and where long-term planning could actually result in evolutionary success.

This may be too short a time-scale to effectively modify our innate psychology, but it may have allowed us to create cultural institutions that counteract our typical short-sightedness. Since, once again, inaction is most prevalent when we’re facing activities without strong cultural pressures, this may suggest that our gap of inaction is due to defaulting to our ancestral, myopic approach to life.

How Can We Get Better at Taking Action?

This subject, why we struggle to take action and how we can improve it, is one that fascinates me. Both because it seems so simple on the surface (“Just do it.”) but so complicated underneath (what do you do when “Just do it” doesn’t work?).

Traditional approaches to this problem have often focused on human will as single thing. But the reality is that our minds are fabulously complicated things, with many different integrating control mechanisms, both conscious and unconscious. To take action, then, you need to not only have new inputs to your conscious mind to nudge you in the right direction, but those nudges need to translate into all the other control systems you possess to keep you headed in that direction.

I have a lot of remaining questions:

- Are there different types of inaction, or do they all have a similar core explanation?

- What separates everyday inaction from the clinical difficulties people who suffer depression or anxiety face?

- Are these simply extreme versions of the slumps and avoidance we all face, or are they separate mechanisms?

- What points in the system are most flexible for adjusting long-term action for the least amount of effort?

As I learn more, I’ll do my best to share it with you.

Conversion Rate Optimization Made Easy

Comments

Post a Comment